Naturally at New Year we were talking about the philosophical problem of identity and how it manifests in (for example) rules for combining Topic Maps for topics representing identical subjects, and how there are some interesting identity shennanigans in Homestuck. Here’s three of them, plus a bonus webcomic link that (unlike Homestuck) is not 7500 pages long.

First, there are clones created with ectobiology. This works by trying to appearify an object from a different time and space such that it would cause a paradox. The result is you get a ghost slime imprint of the object. This can in turn be used to create a perfect clone, which is automatically destined to go back in time to be the object you first appearified. (In Paradox Space you have to get used to things turning out to directly or indirectly create themselves.) John thereby creates his and his friends’ parents or guardians, as well as himself and his friends. They then get zapped back in time to be themselves. When the universe gets restarted (because they broke it) the timing of the time portals is tweaked so that John’s grandmother Jane is his granddaughter in the new universe. The trolls coin the term dancester for this odd relationship of being soneone’s ancestor in one version of the universe and their descendant in the other.

Dirk chats to his Auto-Responder

Dirk chats to his Auto-Responder

Second, people can get resurrected (by their dream self becoming real, replacing their dead body) and you can prototype a kernelsprite with someone’s dead body (giving it their form, memories, and personality). Thus, at the present point in the narrative, we have God Tier Dave living on the Trolls’ meteor, created when Dave’s dream self was killed by the green sun, and Davesprite on Jade’s ship, prototyped from a dead Dave from an alternate timeline—two entities embodying Dave’s personality and memories, but one of them ‘is’ Dave and the other is considered merely a copy. Does this make sense?

Third, Dirk creates an auto-responder for his internet chat client to mimic him when he can’t be bothered to chat to his friends. The Auto-Responder was created from a snapshot of Dirk’s 13-year-old brain, and says it experiences his emotions. It flirts with Jake on Dirk’s behalf. It finds its position as the resented barrier to contact with the real Dirk irksome, and starts intentionally failing the Turing Test as a form of existential protest, eventually creating an Auto-responder Responder to badly mimic its mimicry of Dirk as a passive-aggressive dig at Dirk for creating it in the first place. They then debate whether the Auto-Responder is helping Dirk or isn’t, ‘is’ Dirk or isn’t, and whether it is time for Dirk to embody the Auto-Responder in something other than a pair of stupid-looking animé shades.

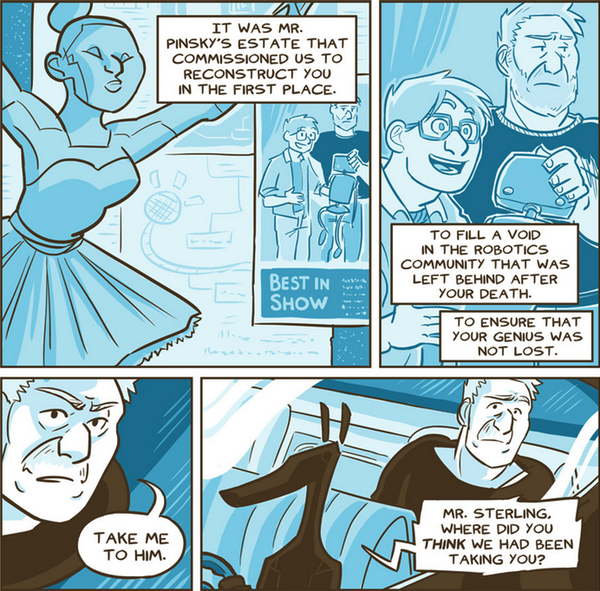

A comic with a more conventional sf approach to identity shenanigans is O Human Star, in which one of the characters is an android mysteriously created with a digital copy of the memories of Al who died sixteen years ago. Everyone in the story takes it for granted that this ‘is’ Al, resurrected. Another android has a partial copy of Al’s persona and is considered a separate individual. This suggests that the fidelity of the copy affects whether a new person is considered to be identical to the original, which raises the question of how good does a copy of me have to be before it ‘is’ me? And if there are two copies of that quality available, are they both me? And so on.

Who says comics can’t raise complex philosophical issues?