Content-Management Systems (CMSs) are designed to facilitate the collaborative editing of a web site by domain experts. Unfortunately some management structures make CMSs useless or worse, leading to wasted effort. Here’s why.

1. How CMSs are Supposed to Work

Drupal is as good an example as any. It has a standard workflow that is designed to be useful in the common case where content is continually updated: each node can be drafted separately and only published when ready; new revisions of individual nodes can be worked on while the old revision is still the published one; the default front page is a list of latest additions; nodes can be tagged with keywords, and keywords used to browse nodes by subject.

With these basic building blocks you can create a site in the styles that are common on the web—an up-to-the-minute news blog, or a collection of textbook pages with a ‘what’s new’ page to encourage regular visits, a product catalogue with shopping cart for e-commerce, a mess of forums, and so on.

The Drupal approach has a fairly lightweight approach to what consultants call ‘workflow’; the assumption is that improvements to the site are being continually integrated, and that the site editors are empowered to decide whether a node is fit for publication. This is reasonable since these are prerequisites of a successful web site.

2. A Caricature of Government Web Site Management

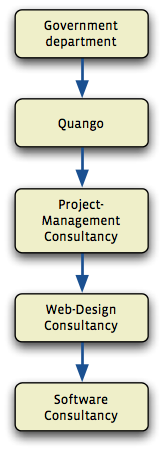

The government delegates responsibility for areas of policy to quangos; these in turn subcontract web sites to project-management firms, who subcontract to web-site design company, who subcontract the building of the site to a software company, who in turn employ a developer or two to do that actual work.

Subcontracting means fixed-price contracts to try to mitigate the RISK of project overruns, which entails the site being updated in big, elaborate releases, rather than continual small changes. The release is specified in a specification in Microsoft Word format, mailed back and forth as the details are thrashed out. The specifications lump changes to the site’s content together with new features, which is how I end up doing text corrections alongside intricate programming jobs.

Where large amounts of new content are to be added, they might be provided as a folder full of Microsoft Word documents or a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet with one row per new resource. Or, more likely, the promise to provide them during the development cycle.

Another thing required to try to mitigate the RISK created combining so many disparate changes in to one release is the creation of a staging site that can be exhaustively tested (user acceptance-testing, or UAT) before going live.

3. How Can it Possibly Go Wrong?

One problem with several-month-long fixed-price contracts is that you end up with a site that is updated only a few times a year—the opposite of what is recommended if you want users to return to your site more than once or twice, let alone make it the centre of their on-line existence, which is what all these quango-devised sites aspire to be.

There is also the complication that no-one in government does anything unless harassed over the phone. So after nine months of consultation, there is six weeks left for development, and signed-off specifications don’t actually turn up in the developer’s inbox until the night before shipping. The copy will not have been proof-read, so new versions will be hastily mailed to us during the UAT period.

By way of illustration, at one point I had four spreadsheets; three of

them were named Resource Library_21Nov2009_FINAL_rev2.xls. By the time we had finished UAT, more or less every task had been done twice: first from the signed-off specification, then again when change requests countermanded it.

4. Why Drupal is Helpless to Help

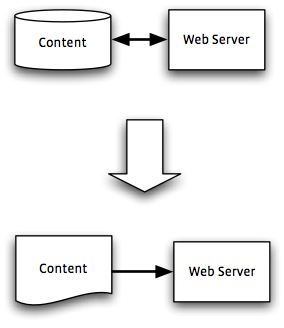

A complete separate server and database will be required for the staging site so that there is no RISK of changes on the staging site affecting the live site. This causes trouble because systems like Drupal store forum posts contributed by users in the same way as pages provided by the site editors; we end up with two Drupal sites whose databases must be merged to make the new live site. This is incredibly finicky and fragile, and if it goes wrong, chunks of content might be destroyed.

The alternative is to have a process where the developers make copious notes whenever they change settings or add content to the staging site, and then the night before the launch day, repeat these steps without error on the live site. In each case we have the perverse situation that after all that frenetic testing and the final sign-off of the site, we begin a deployment process that might easily wreck the whole thing.

The other problem is that they do not use the CMS to edit the content. Instead programmers are obliged to copy and paste text from Word or Excel documents for them. This is tedious and error-prone.

To try to reduce both the tedium and the risk of careless errors, a programmer worth their salt will write a program to parse the spreadsheet and generate the CMS nodes automatically. The problem here is that the nature of Drupal is that information describing one page is scattered between a bunch of database tables. Drupal has a hook system that allows for any stage of editing or saving a node to be modified by any of the modules installed. To add a node you should call a succession of PHP functions so they can call all the hook functions. So in a recent case I added a HTTP API for adding nodes, just so my Python program could create nodes via the PHP API. Now while this was more entertaining (to me) than copying and pasting the documents by hand, it also had the advantage that I could replay it against the live database to do the deployment much more reliably than it would have been if I had done it by hand. While in this case there was a happy ending, it was much more work than would have been required with a simpler (not-CMS) web server.

The upshot of all this is that the content-management system cannot help much with updating the site, and can even get in the way.

5. What to Do?

I can see two obvious approaches to addressing this problem:

Option A: A New Kind Of CMS

Invent a content-management system that better suits their process:

- It has an explicit concept of changes coming in waves;

- Content from all versions share the same database, with a special hostname being used to show the next version of the site;

- Updated code for the next version does not interfere with the current version;

- Content producers can draft and comment on new content in a way that requires no more effort than just mailing attachments to each other.

The last point is crucial, and might be achieved by making the CMS able to parse word documents and participate in mail exchanges itself, or by creating plug-ins for Microsoft Word to co-ordinate it with an on-line database (at which point you end up reinventing SharePoint).

The first approach will require a great deal of cleverness to get to work, and it entails rethinking the way the quangos work altogether to be organized around the web first, and office paper-shuffling second. this would require concerted effort from all levels of the hierarchy to rethink office work, which might be a bit too much to expect within a short timeframe.

Option B: Spreadsite

In this alternative, we instead acknowledge that collaboration and review inevitably happens outside the web site, and therefore we drop the CMS altogether, instead devising a web site that uses the spreadsheets and word-processor files directly.

This approach is much easier to put in to practice. So much so, in fact, that I have already created my own proof of concept called Spreadsite. The idea is that deployment works by simply placing files in the right folders on the server, with no complicated database jiggery-pokery. The software examines the column headings to work out which are titles and which are keywords for navigation. My prototype is just a proof of concept: it displays a ‘resource library’ (a twentieth-century term for a list of links to other web sites), and includes simple navigation based on keywords.

I this just a parody? Once I had built it—thanks to the wonders of Django, it took an afternoon’s work, no more—I discovered that this is actually not that bad way to edit this sort of site—I could make changes in the list of items in Numbers, save as CSV, and hit Reload in the browser window to check the results. Much faster than using a web form!

Could this be used seriously to implement a real web site? The ideal would be for the Excel spreadsheet to be used exactly as supplied by the customer, thus requiring no additional work when they inevitably come up with an urgent replacement. Using the spreadsheet verbatim have another benefit: it would establish firmly the responsibility for correct spelling, punctuation, and grammar with the customer. To make this possible would require more programming work, but less time, I suspect, than would be spent on fighting the CMS would take.