Back in the 1990s I used RDF as the model for a metadata database of on-line resources for people living with HIV and AIDS (the SEAHORSE project. Much water has flowed under the metaphorical bridge since then, but yesterday I found myself seriously using RDF for the first time in ages and I thought I would briefly comment on how the state of the art has advanced over the intervening decade.

Back Then

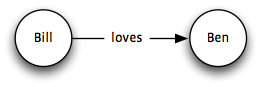

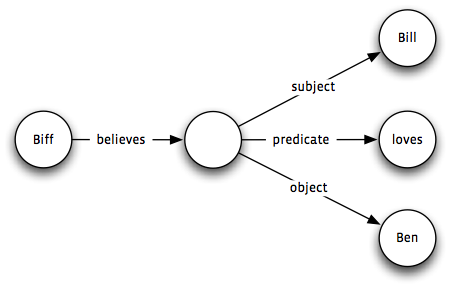

There were experimental ‘RDF engines’, but none available for the platform I was obliged to use (Microsoft IIS running on Microsoft Windows, with Microsoft SQL Server as the storage). So I rolled my own, compromising slightly with the purity of triples. For example, our system wanted to include info about who was asserting facts about resources. The RDF way—in 1999—was to reify the statement. Thus instead of storing a simple subject–predicate–object statement like so:

you instead store a statement about a blank node that represents your first statement through three more statements:

Stored as triples, this leads to a combinatorial explosion in the number of triples needed to store any fact. Since all statements solution was to represent statements as quadruples, with an extra attribute representing the authority for the statement (which I called an annotation set, lifting nomenclature from some other long-dead metadata project).

Naturally it made sense that statements lived in different database tables depending on whether they were associations between resources (e.g., between a category and the resources tagged with that category) or were scalar attributes of resources (e.g., titles, descriptions, etc.). Where literal values were multilingual the quad became a quintuple so that the language identifier could be included.

There being no tools for processing, querying, or aggregating RDF available at the time, the only way to get at this data was through navigating the site. After a couple of months I had things set up so I could visit the nodes and see the data and links to associated nodes’ pages, showing that the application objects worked. Then I waited for the designers to come up with the production UI for the application. In the end various things didn’t happen and we ran with what I had created.

There were two main barriers to making SEAHORSE user-friendly:

-

The structure imposed by the very simple metadata engine I had created was fairly rigid, and

-

Once they had seen my simplistic metadata navigator, most project partners could not imagine a different UI.

Since then I have believed that it is important to start sketching out user experience and site navigation before designing the underlying data model.

One of the side effects of having pages mapped on to nodes and links between them was that with a bit more template kludgery, we could use it as a CMS. Thus my software was adapted by Oxinet to make the first version of the NICE web site. Oxinet went on to create their own Seahorse.NET, a CMS that has no code in common with my SEAHORSE codebase, but retains some of the concepts.

Topic Maps

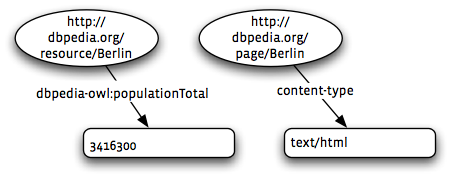

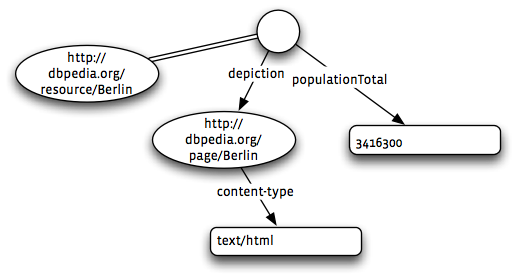

In another project I was stuck with doing the metadata and I had a look at ISO Topic Maps, especially XTM. Topic maps cover similar territory to RDF. The main difference is that Topic Maps impose more structure on the data. For example, XTM distinguishes between a URI used to identify a subject and a URI that is the subject. I still find the way RDF conflates the two a little disconcerting.

In a topic map you would have a topic—something a bit like RDF’s concept of plank node—and it would specify http://dbpedia.org/resource/Berlin as a subject indicator of this topic, and http://dbpedia.org/page/Berlin as an occurrence of this topic. The difference is that topic-map engines know that topics with the same subject indicator are the same topic: no need for an extra layer of ontologies and theorem-provers on top to handle basic merging.

The main problem I had with using XTM as the basis of an application’s metadata was that I was forever having to write code to satisfy fiddly aspects of the XTM data model that were not relevant to my application. Also, the XML representation is intentionally very verbose. I used a lot of code generation to manufacture XTM files from simpler source files.

The problem (again) was that I spent a lot of effort creating a not-very-functional topic-map engine, because at the time (2002) there were no readymade engines available to me.

Python Makes RDF Fun

Recently I started on a Django application to implement a work planner + work log. As I add features I may need to edit the model from time to time. Rather then write a succession of migration scripts in SQL, I want to be able to dump the contents of the application to a file and then load it safely in to a new and improved version. This is also how I imagine doing deployment and backups.

As it happens, one of the company directors has recently discovered a new technology called RDF, a kind of semi-structured sub-relational database-like storage-interchange methodology for synergistically commingling disparate, heterogeneous databases. Awesome. So I thought I would see how the state of the art has advanced in ten years.

I have been keeping half an eye on the progression of the Semantic Web from being an obscure distraction to being an esoteric distraction with lots of talk of how ontologies and theorem-provers built on top of RDF will make RDF the basis of machine intelligences that roam the internet processing natural-language queries.

There is also a pragmatic profile of RDF called Linked Data, advocated by Tim Berners-Lee. There has also been work on extracting RDF data from normal documents (GRIDDL, RDFa). Microformats like FOAF are being mined by the RDF community to provide commonly-agreed vocabularies.

Meanwhile, engines for processing RDF triple-stores exist for most language platforms. The default for Python appears to be rdflib. This covers the basics: you can create a graph with or without backing storage, or parse existing ones in a variety of formats—RDF being an abstract syntax, there are many concrete syntaxes popular with different constituencies—and interrogate a graph using the language SPARQL.

(Aside: I just stumbled across RDF support for Drupal, complete with SPARQL.)

The availability of a readymade engine transforms the cost-to-benefit ratio of RDF. It is now a relatively simple matter to write code to copy my application objects in and out of a graph. If I add features in future versions of the software, the importer will be extended to substitute default values when presented with a graph missing the new data. Compared with the alternative of a bespoke XML or plain-text serialization format, I write less code now, rather than more. And when by boss asks how he can perform ad-hoc queries against my application’s data, I can point him at the RDF URL. Alas! he will then insist that it is useless unless he can run ad-hoc queries in Microsoft Access, but the thought was there.

I was considering whether I want to make it generate the RDF through Python’s reflection and introspection features rather than writing a function afresh each time. It might get a little complicated if I want to use standard URIs for concepts that have them and only use made-up ones when actually necessary.

Semantic web?

Of course RDF support is not itself sufficient for the semantic web to spring in to life in all its omniscient glory, any more than XML is sufficient to create a word processor—but can be a useful tool along the way.

Still, as a super-flexible format for encoding information it’s useful enough for my purposes. I’ll check how the Semantic Web is getting on in another ten years.